Ontario’s rental landscape is unique – a mix of strong tenant protections (like rent control and a dedicated Landlord and Tenant Board) and detailed obligations for landlords. If you’re a landlord in Ontario in 2025, whether in downtown Toronto or a small town, you need to know the Residential Tenancies Act, 2006 (RTA) inside-out. This guide will walk you through key points: from setting up leases and collecting deposits, to the do’s and don’ts of rent increases, maintenance duties, and legally ending a tenancy. We’ll keep it conversational and practical, so you can stay compliant without getting a law degree. Let’s dive in, eh!

Understanding Ontario’s Rental Framework

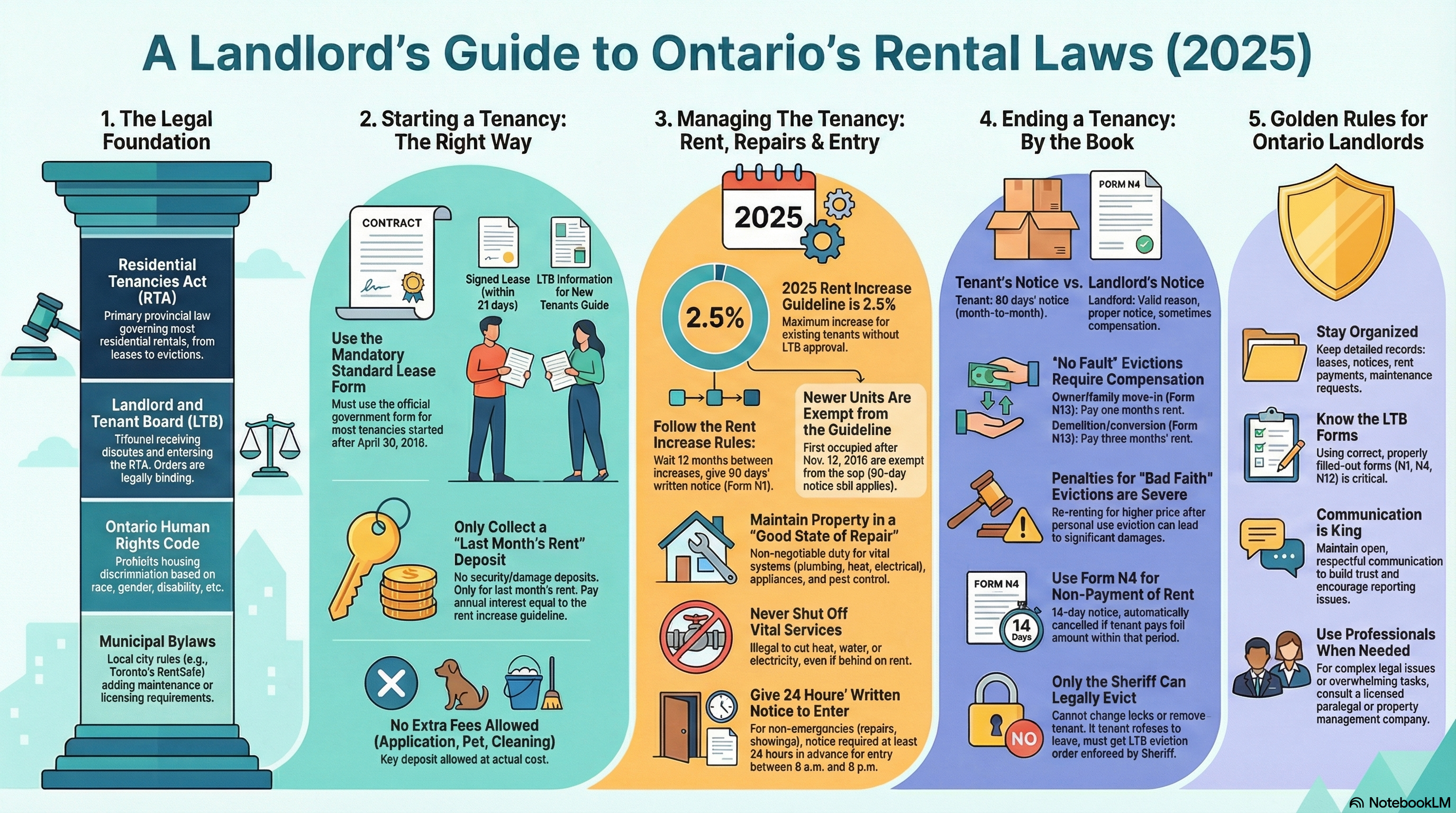

Residential Tenancies Act (RTA): This provincial law governs most residential rentals in Ontario. It’s the rulebook for landlord-tenant relations – covering vital topics like maintenance standards, rent regulations, deposits, evictions, and more. The RTA is quite comprehensive (it replaced older legislation in 2007), and it’s periodically amended. As of 2025, recent notable changes include tweaks to rent control exemptions (more on that later) and new obligations like providing information to new tenants. Always ensure you’re referring to the current RTA or reliable summaries of it.

Landlord and Tenant Board (LTB): This is the tribunal (under Tribunals Ontario) that resolves disputes and enforcement of the RTA. If you need to evict a tenant, claim rent arrears, or a tenant files a complaint against you (like for maintenance or harassment), the LTB is where it gets adjudicated. The LTB has application forms for various issues (N forms for notices, L forms for landlord applications, T forms for tenant applications, etc.). They also publish brochures and guides to help both parties understand their rights . An LTB order is like a court order – enforceable and binding, though there is an appeal route to a real court (Divisional Court) on legal errors, but that’s rare.

Human Rights Code: Ontario’s Human Rights Code prohibits discrimination in housing based on protected grounds (race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, family status, disability, etc.). Landlords cannot select or evict tenants in a discriminatory manner. For example, you can’t refuse someone because they have children or because of where they were born. Advertising a rental as “suitable for single professionals only” could be viewed as discriminating against families, which is a Human Rights violation. The Ontario Human Rights Tribunal handles such complaints, separate from the LTB.

Local Rules: Some Ontario cities have additional bylaws affecting rentals. Toronto, for instance, has a RentSafe bylaw requiring apartment building landlords to register and meet certain maintenance standards. Other cities might have licensing for secondary suites or student rentals. Always check municipal requirements in addition to provincial law.

So that’s the structure: RTA + LTB for the tenancy specifics, and overarching human rights and local bylaws in the background. Now, let’s get to the meat of how to operate under these rules.

Starting a Tenancy: Leases, Deposits, and Documentation

Written Lease and Standard Form: Ontario now requires that for most residential leases entered after April 30, 2018, you must use the government-provided “Residential Tenancy Agreement” Standard Form . This standard lease form is a fillable template that ensures all essential clauses and mandatory info are covered. If you don’t provide a written lease or refuse to use the standard form when the tenant asks, the tenant could even withhold rent (in some cases) or the tenancy could become periodic by default. So just use it – it’s available online in PDF and in multiple languages. Of course, you can add additional terms in the appendix provided they do not contravene the RTA. If any term you add contradicts the RTA, it will be void . For example, a “no pets” clause is void (Ontario law says you cannot ban pets, except in condos where condo rules prohibit them). A clause that “tenant will be responsible for all repairs” is also void because maintenance duty is squarely on the landlord by law. So stick to reasonable additional terms (like maybe stating rules about snow shoveling for a house rental, or key replacement costs) – and double-check their legality.

Once signed, you must give the tenant a copy of the lease within 21 days . Also, since 2021, for any new tenancy, you as landlord must provide the tenant with an information guide (the LTB has a brochure called “Information for New Tenants” ). This guide explains rights and responsibilities. Failing to provide it might lead to delays if you later try to raise rent or evict (the LTB may ask if you gave the guide).

Rent Deposit (Last Month’s Rent): Ontario landlords are allowed to collect a rent deposit – but strictly for the last month’s rent (or last week’s, if rent is weekly) . You cannot ask for a “security” or “damage” deposit on top of that . That’s right: unlike most places, you generally cannot collect a damage deposit in Ontario. The only deposit is for last month’s rent, and it must be applied to the tenant’s rent for their final month. It’s common practice to collect first and last month’s rent up front when a tenant signs the lease (first month’s covers the first period, last month’s is held on account). Important: that last month’s rent deposit does not get used for repairs or cleaning – if the tenant damages something, you have to pursue them for costs via the LTB or agreement, you can’t just take it from a deposit .

Additionally, you must pay the tenant interest on the rent deposit every year, equal to the rent increase guideline . Essentially, the deposit’s value must be maintained. In practice, since the guideline has been around 1-2.5%, most landlords just apply the interest as a credit toward the tenant’s last month rent or to increase the deposit to match any rent increase. For example, if rent was $1000 and you hold $1000 as deposit, and the guideline was 2% that year, you owe $20 interest. Typically, when you serve a rent increase notice, you’d also request the tenant to top-up the last month deposit by that $20 (so it becomes $1020) or you pay them $20 interest directly. Often it’s easier to credit it against a rent payment or add it to deposit, which the law allows . Just don’t forget about this – tenants will remind you, since the LTB guide tells them they are owed deposit interest.

Key Deposits and Extra Fees: The RTA prohibits landlords from charging any fees except: rent, rent deposit (last month), refundable key deposit (at actual cost of keys), and parking (if applicable) or other services as part of rent. You cannot charge application fees, “pet fees,” cleaning fees, etc. It’s all rolled into rent. A key deposit is allowed only if it’s reasonable and refundable – e.g. charging $50 for a fob and then returning it when the tenant gives the fob back.

Unit Condition and Documentation: While Ontario doesn’t mandate move-in inspection reports like some provinces, it’s highly advisable to do one. Document the unit’s state at move-in with photos and a checklist, and have the tenant sign off or send them a copy. This will help later if there’s a dispute about damages. Ontario landlords must keep the place in good repair regardless, but documenting initial condition protects you from false claims of pre-existing damage.

Vital Information: Ensure your tenant knows how to reach you (or your property manager) for repairs or issues. Ontario law requires that in the lease or by written notice you give the tenant an address for service (where they can send legal documents/notices) – usually your mailing address. If you change addresses, update them. Also, provide emergency contact if possible.

Getting the tenancy off on the right foot sets the tone. Use the standard lease, be transparent about all terms, and do everything by the book. The tenant will see you take your role seriously and likely reciprocate.

Rent Control and Increases in Ontario

Ontario is known for its rent control system. Here’s how it works as of 2025:

Annual Guideline: Each year, the Ontario government sets a rent increase guideline – the maximum percentage you can raise rent for existing tenants without special permission. This guideline is tied to the Consumer Price Index (inflation) but capped by legislation. In recent years, the guideline was capped at 2.5% even if inflation ran higher. For 2025, the guideline is 2.5% – in fact, it’s been 2.5% for a few years in a row, which is the maximum allowed under current law. (There was talk about potentially lifting the cap if inflation stayed high, but so far it remains.)

12-Month Rule & 90 Days Notice: You can only raise rent if at least 12 months have passed since the tenant moved in or since the last increase . And you must serve a Notice of Rent Increase (Form N1) at least 90 days before the effective date . So, if a tenant started May 1, 2024 at $2000, you could raise rent as of May 1, 2025 by up to 2.5% to $2050, but you’d have to give them the N1 by January 30, 2025. If you miss that window, you have to wait – you cannot retroactively charge rent increases.

Exemptions – Newer Units: Not all rentals are subject to the guideline. Thanks to an exemption introduced in November 2018, units that were not occupied for residential purposes as of Nov 15, 2018 (i.e., new constructions or new conversions after that date) are exempt from rent control . That means if you own a condo first occupied in 2020, you actually can increase the rent as much as you want (market permitting). However – you still must give 90 days notice and only once per 12 months. It’s just the percentage cap that doesn’t apply . That said, there’s been political debate on this exemption. It could be changed in the future, but currently in 2025 it’s still in effect. Also exempt are units in buildings that have less than 3 units where the landlord lives in one (so-called “landlord’s own unit in triplex or duplex”), and certain social housing, etc. The majority of private rentals in large buildings are under rent control unless they’re brand new builds after 2018.

Above-Guideline Increases (AGI): Landlords can apply to the LTB for an increase above the guideline in specific cases – mainly if you have made major capital expenditures (big renovations or repairs like replacing a roof, new elevators, etc.) or had extraordinary increases in municipal taxes or utility costs . The LTB might grant an extra few percent spread over a couple of years. There’s a whole process with tenant notices and hearings. Note there’s a cap that an AGI cannot exceed an additional 3% beyond the guideline in any year , and AGIs have become harder to get as the LTB scrutinizes if the costs were really necessary. Many small landlords never use this; it’s more common for larger apartment buildings doing major upgrades.

No Increase during a Fixed Term unless in Lease: If you signed a fixed-term lease (say one year) with the tenant, you cannot raise rent until the term is over unless the lease itself had a clause allowing an increase (which residential leases typically don’t, aside from maybe parking fee changes). So usually you’d wait until the year is done and it becomes month-to-month, then apply the increase with proper notice.

Rent Freeze History: Note that in 2021 the Ontario government froze rents (0% guideline) due to the pandemic hardship. That was a one-time freeze. By 2022 it resumed (guideline ~1.2%), and 2023-2025 guidelines have been at the 2.5% cap because inflation was higher. Keep an ear out: in unusual economic times, the province can legislate changes to the guideline or freezes.

Other rent rules: You cannot charge for additional occupants after a tenancy begins. For instance, if your tenant has a baby or has their cousin move in, you can’t just raise rent or add a fee – not without going through proper increase timing and guideline limits. Some landlords mistakenly think they can increase rent because “more people are using the unit,” but Ontario doesn’t allow that mid-tenancy (except perhaps via AGI for utility cost changes, but not directly per person).

Also, a landlord cannot require post-dated cheques or automatic payments. You can ask, but if a tenant prefers to pay monthly manually, that’s their right . And you must give receipts if the tenant asks, for any rent payments or deposit received .

Keep in mind the spirit of rent control: It’s to provide predictability for tenants. Smart landlords in Ontario plan for modest annual increases. Don’t skip increases for many years and then expect to impose a huge one – you’ll be stuck at the cap and essentially losing ground to inflation if you delay. Regular, reasonable increases (with good communication) are generally accepted by tenants, whereas a sudden large jump (even if legally permissible in an exempt unit) can lead to tenant turnover or bad blood. So strategize accordingly.

Maintenance and Repair Obligations

Landlords in Ontario have a broad, non-negotiable duty to maintain the rental property in a good state of repair and comply with all health, safety, housing, and maintenance standards. This is a fundamental part of the RTA (see section 20 of the RTA). It doesn’t matter if the tenant knew of issues when moving in or even caused some of them – the landlord is responsible for making sure the place is livable and up to code.

Key aspects of this duty:

State of Good Repair: The property’s structure and vital systems must be kept safe and operable. Roof shouldn’t leak, windows should open/close safely, plumbing and electrical should work, heat in winter must be provided (usually at least 20°C per local bylaws). The tenant should always have hot and cold water, and the appliances provided should function. If something breaks due to normal use or age, it’s on you to fix it. For example, if the fridge dies or the furnace goes out, that’s your responsibility – even if it means a significant expense. Build maintenance costs into your financial plan for the property; it’s not optional.

Essential Services: In Ontario, landlords cannot withhold or shut off vital services (water, heat, electricity) even if the tenant is behind on rent. Cutting off utilities to force payment or eviction is illegal “self-help”. If utilities are in your name and the tenant pays a portion, you must keep them running and then chase rent or utility costs through the LTB if needed – not by turning off the lights.

Repairs and Timing: The RTA doesn’t specify exact timelines for every repair, but the expectation is “reasonableness.” Urgent issues should be addressed urgently (no heat, major leaks – same day or within 24 hours). Less urgent issues should still be handled in a timely manner (a broken closet door might not be an emergency, but you shouldn’t wait months – a couple weeks maybe). If a repair is going to take time (like ordering a part or scheduling a contractor), communicate that to the tenant. Lack of communication causes many disputes. Tenants have the right to seek remedies if you’re not doing necessary repairs. They can file an application for a rent abatement, or even do repairs themselves and deduct in some situations (though that’s not formally allowed without LTB approval, some will do it and then it gets sorted at a hearing).

Tenant Responsibilities: Tenants must keep their unit clean and not willfully damage anything . They aren’t responsible for normal wear-and-tear. If a tenant causes damage (beyond normal use), they are responsible to pay for it. But you as the landlord should still arrange the repair to ensure it’s done right, then bill the tenant or file at LTB if they don’t pay. For example, if a tenant’s kid breaks a window, you’d fix the window (quickly, for safety) and then either come to an agreement for the tenant to reimburse, or take it out of their last month rent deposit with consent to use it (not normally allowed without consent), or file at LTB when they move out. You can’t ignore a broken window because “it’s the tenant’s fault” – that violates safety standards and your obligations.

Pest Control: Bedbugs, roaches, mice – unfortunately, these can occur even in clean buildings. In Ontario, landlords are generally responsible for ensuring pest infestations are addressed. Tenants are required to cooperate (preparing unit for treatments, etc.), but you likely have to hire pest control and cover the cost. Many municipalities have property standards that include keeping units free of pests. If a tenant’s poor housekeeping caused it, you might have a case to charge them or evict if they refuse to remedy contributing behaviours, but you still must tackle the issue.

Bylaw Standards: Ontario cities have property standards bylaws (for example, Toronto’s RentSafe bylaw rates buildings on maintenance). Landlords must follow those as well as the RTA. If a tenant calls property standards or property inspectors and they find violations, you could face orders or fines. Those orders can also become evidence at the LTB if a tenant files a maintenance application.

If a landlord fails maintenance obligations, tenants can get orders from the LTB ranging from rent reductions, refunds, or requiring you to do repairs by a deadline. In serious cases, the LTB can allow the tenant to withhold rent until repairs are done or even terminate the tenancy (rare unless it’s truly uninhabitable). There’s also a section where the LTB can prohibit you from renting it out at a higher rent to a new tenant until you fix outstanding issues – a measure to stop landlords from ignoring problems for current tenants then just re-renting at a higher price.

Bottom line: Stay on top of maintenance. Schedule regular check-ups (with proper notice) for things like furnace, filters, smoke alarms (Ontario law requires working smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors – provide and replace batteries as needed). Keep lines of communication open so tenants report issues early. It’s often easier (and cheaper) to fix a small leak now than a big flood later. Plus, a well-maintained property retains value and keeps good tenants longer.

Entry and Privacy Rights

In Ontario, once you rent out a unit, you can’t just pop by unannounced – the tenant’s right to reasonable privacy is protected. The RTA regulates when and how you can enter:

24 Hours Written Notice: To enter a tenant’s unit for non-emergency reasons (repairs, inspections, showing to prospective tenants or buyers, etc.), you must give at least 24 hours written notice . The notice should state the date and time (which must be between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m.), and the reason for entry. Email or text is not officially “written notice” unless the tenant has agreed to that method in writing; normally it should be a paper notice delivered to the unit (like slipped under door or in mailbox). Many landlords do use email with tenant consent these days. Regardless, 24 hours is the minimum – you can’t do same-day unless the tenant says “sure, come on in.”

Emergencies: No notice is required if there’s an emergency – e.g., you see smoke, or a water pipe burst and you need in ASAP. Also, no notice if the tenant invites you in at that moment (like they call and say “the stove stopped working, can you come now?” and you come over immediately – they’ve given permission).

Tenant Consent: A tenant can waive the notice or timing requirements by consenting to entry. For example, if they’re home and say “you can come in and fix it now,” that’s fine. Get it in writing or text if possible (“Okay, as per our call, I’m coming by in 15 minutes to fix the tap.”).

Showing to New Tenants/Buyers: If the tenant or you have given notice to terminate (e.g., tenant is leaving, or you’ve legally terminated for sale or own use), you can show the unit to prospective new renters or purchasers. You still need to give 24-hour notice for each showing, unless you reach an agreement for a set schedule (sometimes tenants agree to, say, an open house time). You don’t need to compensate the tenant for showings, but do be considerate – incessant showings can be seen as harassment. Usually, clumping interested parties into a weekly viewing block is better than daily disruptions.

No Harassment or Abuse of Right of Entry: You can’t use entry as a harassment tactic. The tenant has a right to “reasonable enjoyment” of their home. So, for instance, scheduling “inspections” every week with minimal reason could land you in trouble. Landlords have gotten LTB orders or fines against them for abusing entry rights. Always have a genuine reason and don’t overdo it.

Lock changes: You can’t change the locks and not give the new key to the tenant – that’s an illegal lockout. Tenants can change the lock with your permission (and should provide you a key). If a tenant changes locks without permission and doesn’t give you a key, that’s a breach too. It’s best to avoid lock changes during a tenancy unless necessary (lost keys, security issue) and if done, ensure all parties get new keys.

Respecting a tenant’s privacy builds trust. If you are courteous and follow the law when entering (and give proper notice), most tenants will be cooperative and appreciate your professionalism. On the flip side, nothing gets tenants more upset than surprise entries or feeling spied on in their own home – that’s a fast track to conflict, complaints, or them moving out.

Ending a Tenancy: Notices, Evictions, and Your Responsibilities

Sooner or later, tenancies end – maybe the tenant decides to move, or you need the unit back, or problems occur. Ontario’s rules on terminating tenancies are strict. You generally need a valid reason under the RTA to end a tenancy without the tenant’s agreement.

Tenant Giving Notice: If on a month-to-month, a tenant can terminate the tenancy by giving at least 60 days’ noticeeffective at the end of a rental period. So if on month-to-month a tenant wants to leave at end of June, they’d give you notice by end of April. For fixed-term leases, a tenant can’t normally break it early without your agreement or an LTB order (except in specific cases like domestic violence situations where 28 days notice is allowed). They can give 60 days for end of term. Many landlords will negotiate if a tenant wants out early – it’s up to you, but you can’t force them to stay either (worst case you could sue for unpaid rent for the balance, but often better to just re-rent quickly). Always get a tenant’s notice in writing.

Landlord Ending Tenancy (No Fault): If you want to evict because you or an immediate family member (or a purchaser in some cases) want to move into the unit, or you plan to demolish or convert it, those are allowed reasons. The notice required is 60 days and must align with the end of a rental period or lease term . For owner or family move-in (using Form N12), you also have to pay the tenant one month’s rent compensation or offer another acceptable unit . And importantly, you (or said family member) must actually move in and live there for at least a year – this is to prevent misuse. If you falsely evict someone this way (e.g., you said you were moving in but then re-rented at higher rent), the tenant can take you to the LTB for bad faith eviction and you could owe them hefty damages.

For demolition or conversion or major renovations (Form N13), you generally owe the tenant 3 months’ rent compensation or alternative accommodation . Renovation evictions are tricky – you must truly need the unit empty (e.g., going to gut the place). Tenants have a right of first refusal to return after reno at the same rent if it’s a repair or reno, not demolition. New laws in 2021-2022 toughened up on reno evictions to curb abuse.

Landlord Ending Tenancy (For Cause): If the tenant is not paying rent, you can give a 14-day Notice to End (Form N4) for non-payment (or 7 days if they pay weekly). The tenant has an automatic right to cancel that notice by paying all rent owed within 14 days. If they don’t, on day 15 you can file with the LTB for an eviction order. Often, if a tenant is routinely late, you may have to file repeatedly. The LTB might grant them grace or a payment plan (especially for first time). Document everything.

Other “for cause” reasons include: persistent late payment (Form N8 – requires several instances and 60 days notice), interfering with others or illegal activity (Form N5 – 20 days notice, with a chance for tenant to remedy in first 7 days), willful damage (N5 as well), safety threats (N7 – 10 days notice no remedial period for serious cases), etc. Each has specific requirements, and often you need good evidence. The LTB will evaluate if the cause is proven and if eviction is warranted. Ontario tends to give tenants chances to correct behaviour, except in really serious situations.

Eviction Process: Serving a notice (N4, N5, N12, etc.) is just the first step. If the tenant doesn’t move out or resolve the issue, you then file an application to the LTB for a hearing. Only the LTB (or a court sheriff) can legally evict a tenant. If you get an LTB eviction order and the tenant still doesn’t leave, you file that order with the Court Enforcement Office (Sheriff) and they schedule a physical eviction. Don’t attempt to change locks or evict by yourself – that’s an illegal eviction. Tenants can be reinstated and you’d face penalties.

When Tenant Leaves: If a tenant gives notice or is evicted properly and moves out, you have some tasks: do a walkthrough to assess any damages, reconcile any last utility bills if applicable, and return any keys. The tenant’s rent deposit (last month) is typically used for their last month’s rent. If they overpaid (rare), you’d refund the balance. If there are damages beyond normal wear, you may negotiate payment or claim against them at LTB or small claims court. In practice, many landlords just absorb minor damages or cleaning as a cost of doing business, unless it’s significant enough to pursue.

Abandoned Belongings: If a tenant disappears or abandons stuff after eviction, Ontario has rules on how to handle their property (basically, after an eviction order or lawful termination, you must hold belongings for 72 hours during which the tenant can claim them). After that, you can dispose of them. If tenant just up and left mid-lease, be careful – you might want an abandonment confirmation via LTB to be safe before reallocating the unit.

Cash for Keys: Sometimes landlords want a tenant out for a renovation or to raise rent (especially in an older building under rent control). One method is to amicably negotiate a “cash for keys” agreement – essentially paying the tenant to agree to move out. This is legal as long as it’s truly voluntary (no coercion). Make sure to document the agreement. Tenants will often negotiate a few months’ rent worth in exchange for leaving early. It can be win-win: you get the unit back without legal fight, they get some money to help move. But remember, they don’t have to accept. If they say no, you cannot harass them – you’d have to either wait or find a legitimate legal reason to evict.

Ontario tends to favor tenant stability, so always approach terminations carefully. When in doubt, seek legal advice or consult the LTB’s resources. And maintain good relationships; a tenant who’s happy is more likely to cooperate if you eventually need the place back.

Key Takeaways and Best Practices

Being a landlord in Ontario isn’t always easy – margins can be slim with rent control, and the procedures are detailed. But many investors still succeed through professionalism and respecting the rules. Here are some golden tips:

Stay Organized: Keep a file for each property with all documents: lease, rent ledger, inspection notes, correspondence. If an issue arises, you can quickly reference everything. There are digital landlord apps (like RentMouse, Buildium, etc.) that help track rent payments, maintenance requests, and even generate LTB forms.

Know the LTB Forms: Familiarize yourself with common forms (N4 for non-payment, N5 for disturbances, N11 for mutual agreement to end, N12/N13 for personal use or reno, etc.). Using the correct form and filling it properly is crucial. A small mistake (like wrong termination date) can void a notice and force you to start over. The LTB website and guides are helpful.

Communication is King: Develop a good landlord-tenant communication channel. Encourage tenants to report maintenance issues promptly by being responsive and non-judgmental when they do. Many serious problems (mold, pests, water damage) start as minor issues that tenants might hesitate to report if they fear a negative reaction. Show that you’re a responsible landlord who addresses concerns, and you’ll build trust.

Plan for the Long Term: Ontario is not generally a place for quick huge rent hikes or frequent tenant turnover. A steady, long-term tenant at slightly below market rent might be more profitable than pushing rent to the max and facing vacancy or a difficult eviction. Crunch numbers with the assumption that a tenant may stay many years. Budget for increase in costs like property taxes, insurance, utilities – and remember you may only raise rent modestly while those could rise faster. Smart investment strategy includes regular property upgrades to justify the best rent within allowed limits and attract quality tenants.

Use Professionals: If managing becomes overwhelming or you’re unsure of legal steps, consider hiring a property management company or at least consulting a paralegal who specializes in landlord-tenant law (Ontario paralegals are licensed to represent landlords at the LTB). Yes, it’s an extra cost, but could save you from costly mistakes (like a botched eviction that drags on for months).

Respect Goes Both Ways: Treat tenants with respect – this includes respecting their privacy, maintaining a clean and safe property, and being fair in your dealings. In turn, most tenants will respect you and your property. The horror stories usually come when one side stops respecting the other (slumlords vs. bad tenants). Set the tone by being a conscientious landlord from day one.

Operating in Ontario’s rental market means working within a well-defined legal framework. By mastering those rules – and maybe leveraging tools like RentMouse to keep everything on track – you can reduce the headaches and focus on the rewards of property investment. Happy landlording!

Bibliography (Ontario)

Riverview Legal – Residential Tenancies Act, Section 20 (Landlord’s maintenance)

Ontario Landlord & Tenant Board – Guide to RTA and Rent Increases

Ontario Ministry of Housing – 2025 Rent Increase Guideline Announcement

Tribunals Ontario LTB – Brochure: A Guide to the RTA

ACTO (Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario) – Tip Sheet on Rent Deposits

Birds Nest Properties – Landlord Guide: N12 and N13 Notices (Ontario vs BC)